French Tragicomedy

The idea of tragicomedy in drama dates back to the ancient Greeks and Romans, but in France an assumption that elevated tragic characters and low comic ones ought not to share a stage was generally accepted well into the 17th century.

That was not the opinion of Jean Baptiste-Poquelin, the playwright and actor who wrote under his stage name, Molière.

Molière consistently pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in theatre at a time when plays were generally expected not to challenge social conventions or the moral authority of the Roman Catholic church.

Several of his most notable plays were highly controversial when first staged. Tartuffe satirised religious hypocrisy, which outraged the church, and the religious authorities were similarly offended by Don Juan for its sympathetic treatment of an irreverent libertine.

Although the playwright and his company enjoyed royal protection, both those plays were banned, but generally Molière was able to steer a course through sensitive subject matter by making his protagonists ambivalent characters with both comic and serious aspects.

They are the butts of humour, but with sympathetic traits, a notable example being Arnolphe in L’École Des Femmes, the Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe production of which, directed by Stéphane Braunschweig, will be performed at the Lyric Theatre, HKAPA, on February 28 and 29.

The play was first staged in 1662, and at the time was criticised both for suggestive dialogue - deemed in some quarters to be obscene - and because Arnolphe, a comic character, was given soliloquies which according to dramatic convention were the exclusive prerogative of serious figures. Critics also objected to Molière’s apparent sympathy with Arnolphe, who the playwright played himself, considering the character too nuanced for comic purposes.

Molière famously answered his critics with a one act play called La Critique de L’Ecole des Femmes, in which he defended not only the play but the core of his art, with the famous line “il faut peindre d’après nature” – characters must be depicted “according to nature”.

By the time another great French playwright, Edmond Rostand, was writing Cyrano de Bergerac, more than a century later, Molière’s “according to nature” precept could be taken for granted, and his Cyrano is a magnificently complex creation in whom comic and tragic elements are exquisitely balanced.

Rostand’s Cyrano is one of the great tragicomic heroes of theatre. The real life Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac was a contemporary of Molière’s, and the two had one prominent characteristic in common – a big nose.

Molière grew up with the nickname “Le Nez” [The Nose] and in Rostand’s play it is largely that physical feature of Cyrano’s which denies him the role of romantic lead, and provides a springboard for much of the play’s comedy.

Many of the facts of the real Cyrano de Bergerac’s life are unknown, and unknowable, but since Rostand’s play was first staged in 1897 the character has been reinterpreted countless times in translations and adaptations of the play for both stage and screen.

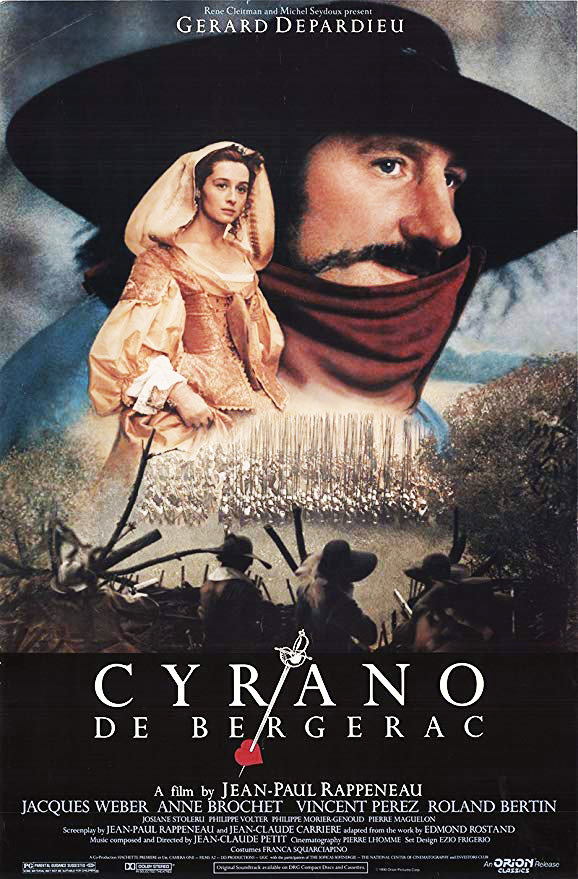

He has, perhaps, been most famously played by another Frenchman with a prominent nose that marked him out as well qualified for the role – Gérard Dépardieu, in Jean Paul Rappeneau’s acclaimed 1990 film. Cyrano was a milestone for Dépardieu, and the international success of the French language movie opened the doors to a Hollywood career in English speaking roles.

The tragicomedy of a man who is eloquent but not handsome, wooing the woman he loves by proxy for a man who is handsome but not eloquent, is a tale which has been translated into many languages – including Japanese and Telugu - with varying degrees of fidelity to Rostand’s original play.

Even before Rappeneau and Dépardieu brought Cyrano under his own name back to the fore for 20th century audiences, Hollywood had based a character on him in a 1980s Hollywood comedy, Roxanne starring Steve Martin, with a happy ending in which the Cyrano based character actually gets the girl.

Rostand’s play has far more wit and depth, and is a fresh source of inspiration to generation after generation of actors and directors.

Both L’Ecole des Femmes and Cyrano de Bergerac were written in verse, and Peter Oswald’s new verse adaptation, directed by Tom Morris, can be expected to capture the spirit of Rostand’s play more faithfully than most of the various reinterpretations that have made it to the screen. These French tragicomedies promise to provide an evening to remember.