The Plague of Our Time: Contemporary Meaning in Camus’s The Plague

In 1947, two years after the end of World War II, Albert Camus’s second novel, La Peste (The Plague), was published in France. The story describes the devastation wrought by a fictional plague on the Algerian city of Oran. Its insights into humanity’s will to survive and the choices people make in the face of fear and death resonated with post-war readers.

Before COVID-19 began to wreak havoc across the globe in late 2019, the Hong Kong Arts Festival was already looking into the possibility of adapting British playwright Neil Bartlett’s 2017 stage version of The Plague. The Festival subsequently commissioned a Cantonese translation from Hong Kong director James Chan Tai-yin and it enlisted Beijing director Wang Chong to stage a production in English. For the two directors and their own respective cities, the unusual circumstances during a pandemic have given Camus’s decades-old text a more personal and contemporary significance.

"I think this act of enumeration or reflecting on what has happened might be precisely the thing that our society is lacking.” ── James Chan Tai-yin

James Chan Tai-yin: “What is it exactly that humanity is going through?”

When Hong Kong director James Chan Tai-yin began translating the play into Cantonese in November 2019, he intended to use it as a vehicle to address the social movement in Hong Kong; it was only with the virus explosion into a pandemic that COVID-19 began to influence his translation of the play. His interest in The Plague stemmed from its treatment of universal human questions and its capacity to reflect the contradictions between the individual and society in recent years. “In unpacking these contradictions, Camus sets off from a humanising perspective; some people even say that he is a humanist. He’ll write from the proposition of: ‘Under these great contradictions, what is it exactly that humanity is going through? What are they learning through personal experience?’ In Camus’s philosophy, reflection isn’t really necessary; we only need to enumerate what we’ve experienced. I think this act of enumeration or reflecting on what has happened might be precisely the thing that our society is lacking.”

Following the widespread outbreak of COVID-19, how did his work on The Plague change? For Chan, the most direct influence was in the play’s use of terminology. Phrases that were previously less familiar to the general public—such as “human-to-human transmission” or “confirmed cases”—have now entered into everyday use and will resonate more deeply with audiences.

The Power of Chemistry

This production casts women in the five lead roles where the original protagonists of Camus’s story were all men. In depicting the impact of disaster on society and the individual, Chan thinks that Camus would often adopt an approach of “dislocation” in his writing. Chan explains: “I think this feeling of dislocation can be used metaphorically with women performing the roles of male characters. Some moments in the play, such as when a female actor says she’s missing her wife, create an almost indescribable dramatic effect that is also a form of alienation. I’m searching for some theatrical effects with which to explore various representations of ‘dislocation’.”

In the play, there are several ensemble scenes, in which the five performers collectively create the atmosphere of a Greek chorus. At the first script workshop of the complete script in October 2020, the gradual unfolding of the story through individual testimony was punctuated by key moments at which the five actors came together to confront the audience and reveal thoughts and feelings that their oral statements could not express. Chan believes that the actors bring a solidarity to the work: “In rehearsal, they express a power that is about ‘surviving together’. They are fundamentally very different actors; I think this state of being ‘different but together’ is beautiful. That beauty comes from their own chemistry; I don’t need to deliberately bring that out.”

For Chan, this is the power of theatre. With the novel ’s frequent references to the solidarity of humanity, what kinds of effects will the flesh-and-blood performance of actors onstage have? This is the unique, personal experience that theatre offers audiences.

Wang Chong: “We need a new language to talk about this moment”

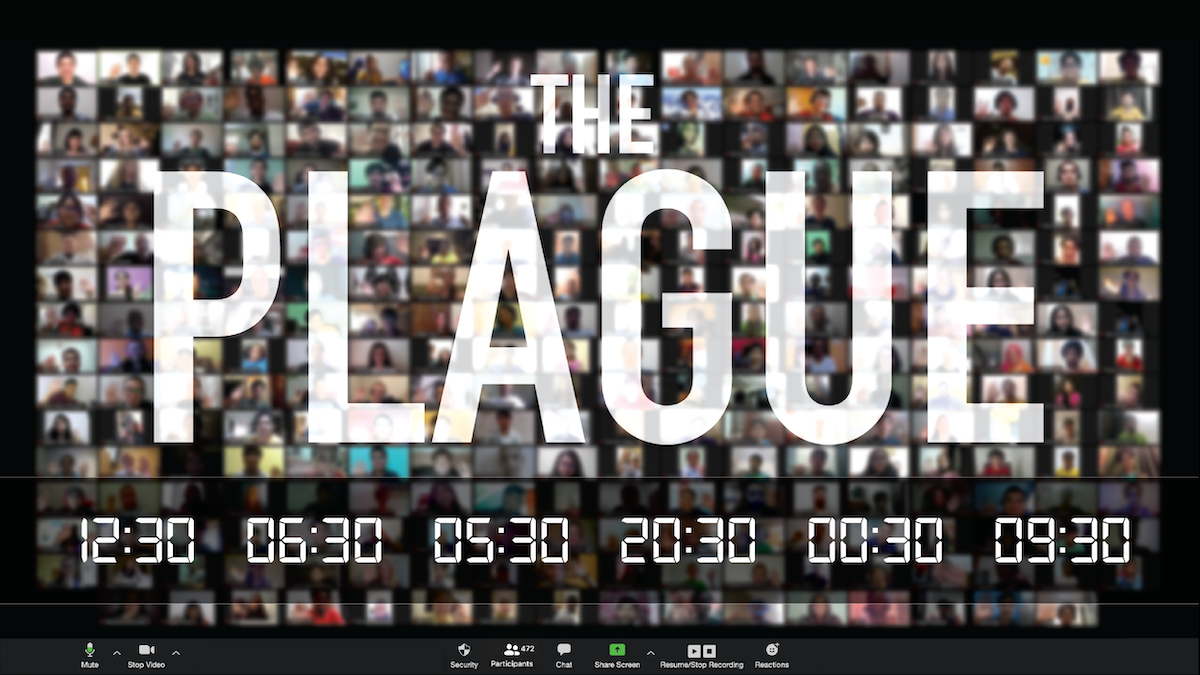

Beijing-based director Wang Chong has previously directed several experimental adaptations of classic works, such as Thunderstorm 2.0 and Teahouse 2.0—updates of 20th-century Chinese classics by Cao Yu and Lao She. Directing the English version of The Plague is another experimental, ambitious endeavour for Wang, due in part to the special format he has adopted—this is an online play in which six actors from six different locations will perform via Zoom.

Wang started reading the script in November 2019, and was instantly captivated: “In the beginning, I chose The Plague because of the anger that arose from the news and the spread of the virus. But afterwards, when the virus became a global pandemic, this anger gave way to anxiety, which was then transformed into a desire to express it. We need a new language, a new format to talk about this moment, this war we are living through. I hope that by using The Plague to closely examine the present, we can manifest a 21st century world.”

"Why does theatre exist? This is my answer: that it should respond to the times.” ── Wang Chong

The Social and Contemporary Nature of Theatre

Wang’s core reason for directing the play is that Neil Bartlett’s adaptation contains profound descriptions of social realities: “Much of the play is situated within the ensemble which contains and presents a variety of viewpoints, including those of officials, a front-line doctor, a journalist, and a businessman. Every level of society makes its appearance; it’s a panorama of society.”

The online format of the play is yet another ref lection of reality. Wang hopes that through his adaptation of The Plague, he can allow viewers to see how the virus has affected multiple cities and their residents. However, the biggest difficulty is coordinating between the multiple time zones. For the actors, the director and his Hong Kong team, it is a challenge, but for Wang “this form of mutual accommodation in terms of timing is a reality of our society in 2020.”

He also sees contemporaneity is an indispensable part of today’s theatre: “Why does theatre exist? This is my answer: that it should respond to the times. Especially when we attempt, present, adapt or direct classic works, we should always keep our eye on the present and let the work be about today. There are many works that—despite being new 2020 productions—adopt an aesthetic or a direction which lacks in the flavour of our time, which is without efforts and marks of our era. I am afraid of theatre becoming like that.” This sort of indefatigable pursuit of the contemporary moment is what allows Wang to create a direct link between classic works and contemporary audiences.

Text

Grace Lam

Grace Lam is an Assistant Editor at the Hong Kong Arts Festival

This article was originally published in the 2021 edition of HKAF’s FestMag

Theatre

The Plague (English version)

As a deadly plague strikes, a large part of the population in a frenetic city is wiped out. After the apocalypse, six survivors testify before a tribunal, each offering a different account of the life-and-death crisis. In this chillingly ruminative production, directed by avant-garde Chinese director Wang Chong, six actors, from six countries around the world, will perform live online. The Plague compels us to take a long, hard look at the outside world and our inner selves during a critical time rife with fear and uncertainties.

Programme details