Behind the Mirror: Ivo van Hove on Theatre and Healing

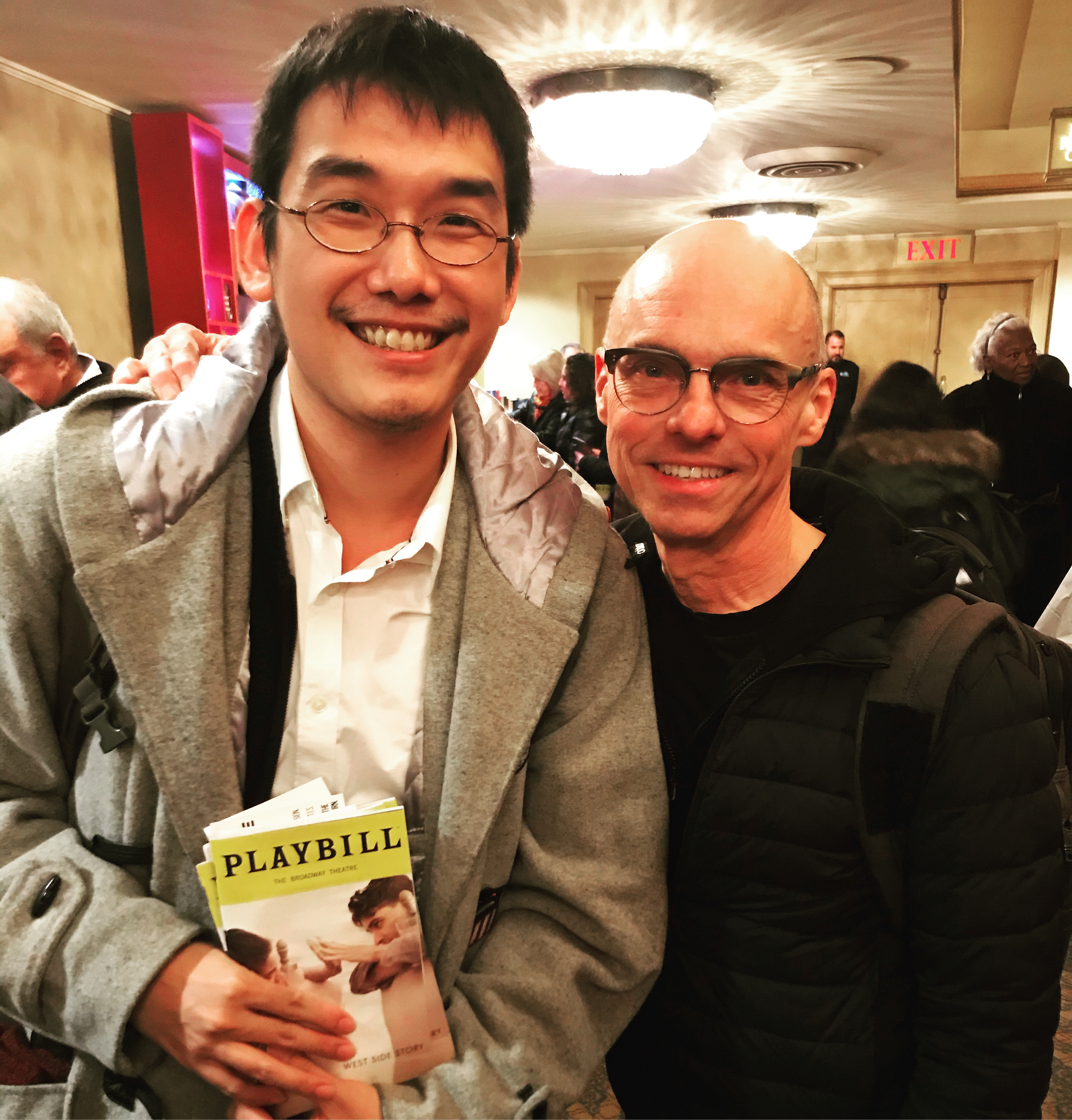

Belgian theatre director Ivo van Hove has been on many theatre enthusiasts’ radar since his production of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge hit at the Young Vic in 2015. Although I was aware of that work, my own road to becoming a serious fan began more recently. In 2017, I had the opportunity to meet Jan Versweyveld — van Hove’s long-term collaborator, scenographer and life-partner — at a four-day masterclass hosted by the West Kowloon Cultural District and Edward Lam Dance Theatre. It was there that I was first able to closely examine and appreciate van Hove’s work.

Van Hove’s emotionally nuanced brand of multimedia adaptations of classic works has conquered the West End, Broadway and international arts festivals, where audiences never seem to tire of his vision. But the root of van Hove’s creativity remains with his Internationaal Theater Amsterdam (ITA) — previously known as Toneelgroep Amsterdam — where he’s served as artistic director since 2001. His productions for the theatre have been hailed by international critics as some of his most refined and vision-forward pieces.

This includes After the Rehearsal/Persona (2012), an adaptation of two Ingmar Bergman films about identity and art, originally scheduled to debut in Hong Kong at the 48th Hong Kong Arts Festival (HKAF) in March 2020. That performance, among many others, was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic — a circumstance that also affected ITA’s spring season, as well as van Hove’s productions outside the Netherlands.

In early June, as Amsterdam made its first steps towards returning to business as usual, I sat down with van Hove over Skype to reflect on his life and work during this time of pandemic and global crisis.

A Sudden Stop

“It was March 13th. It was actually Friday the 13th,” van Hove recalls. “Suddenly, the government at 5:30pm said that all restaurants, all theatres had to shut down immediately, within half an hour. Of course, before, I was aware of the coronavirus. We had been working in New York [on West Side Story], then travelled to Paris and worked with Isabelle Huppert [rehearsing a French adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie]. I also needed to come back to Amsterdam for the revival of The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, so I was in different communities all over the world. I had washed my hands, taken the [health and safety] measures already, but I wasn’t aware that the coronavirus was going to hit that big until Friday the 13th, 11 weeks ago.”

Even without the coronavirus, amidst his tightly packed schedule of openings and revivals in late 2019 and early 2020, van Hove’s adaptation of West Side Story had already proved to be quite the task. His vision to shake the traditional audience’s perspective of why the classic is a classic meant stripping the musical to its violent core, leading to extra-careful treatment of the source material and a gruelling period of rehearsals and previews. With the coronavirus looming on the horizon, opening night was pushed back two weeks due to a cast member’s injury.

Despite the challenges and controversies, the show opened to positive reviews and broke the all-time Broadway box-office records for a single week — more than once. All signs indicated that Ivo van Hove’s West Side Story was destined for a long and fruitful run.

And then, just less than a month after the show’s opening, New York went into lockdown, and Broadway shut its doors. Up until the time of writing, Broadway had still not re-opened, with rumours circulating that it will not be fully functional until next year.

“It was very painful and sad,” says van Hove of the closure. “Of course, my first thought was ‘Oh, what will happen to the young kids?’ All 40 kids that I worked with — including understudies and swings — worked so hard for months and months, six days a week — most of the time seven days a week. Finally, we got it there, and the reception was great. People were ecstatic about it. That’s why, after lockdown, my first thought was ‘Oh Jesus! No one knows what’s going to happen to them.’ Money stopped coming in for them.”

At the ITA, van Hove has been able to continue paying the theatre’s staff with the help of subventions; in New York, it’s a different story. “But you know, New Yorkers, they’re very resilient, with a very positive mind […] The producer is committed to the production and really intends to bring it back once it’s possible.”

Healing in the Theatre

Beyond its central love story, the core of the original West Side Story is about racial prejudice and exclusion. Van Hove’s production strips down the Broadway language of song and dance to question why racism persists today.

The timing couldn’t have been more appropriate. At the time of our conversation, the Black Lives Matter movement had already swept the United States and captured global attention following the death of George Floyd at the hands of the police on 25 May 2020.

Personally, I treat theatre or art as a mirror to life; it’s not just entertainment, but a reflection of who I am, a reflection of the community I am in, a connection with characters and situations that resonate with me. It makes me think about how I should live on when I identify a problem within the world created onstage.

Harold Pinter, when he won the Nobel Prize, said in his acceptance speech, ‘Art and theatre are here to give us a look behind the mirror.’ In the mirror, we see what we want to see, but what’s deep inside us, that is what we don’t want to confront. Racism, for instance, is deep inside us,” he says. “I think Pinter was right, that art is there to look behind the mirror. That is what we try to hide. That is what we try not to acknowledge.

But, says van Hove, theatre is not always about looking into the mirror. “Harold Pinter, when he won the Nobel Prize, said in his acceptance speech, ‘Art and theatre are here to give us a look behind the mirror.’ In the mirror, we see what we want to see, but what’s deep inside us, that is what we don’t want to confront. Racism, for instance, is deep inside us,” he says. “I think Pinter was right, that art is there to look behind the mirror. That is what we try to hide. That is what we try not to acknowledge.”

Many of van Hove’s works recently performed in the US and UK re-examine existing literature that resonate with current local and global political climates. Roman Tragedies (2007) looks at the effect of the media on politicians through Shakespearean characters; Kings of War (2015) further cross-examines Shakespearean world leaders; The Fountainhead (2014) reconsiders Ayn Rand’s controversial philosophy of Objectivism. Yet, even though his work addresses the politics in our lives, van Hove never indulges in political stances. In fact, by simply acknowledging the politics, his works offer audiences a place to heal.

Telling Stories to Survive

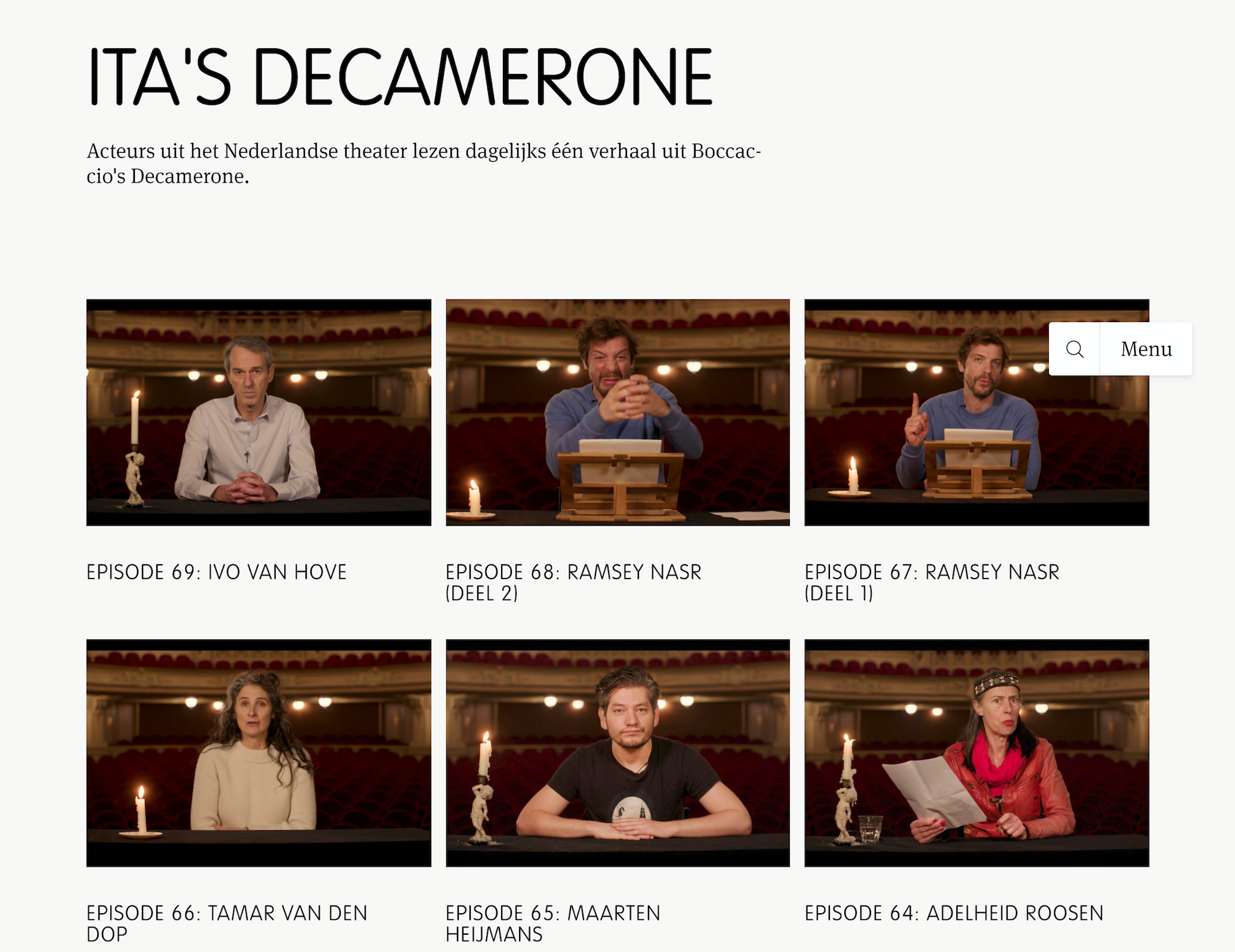

During the lockdown in Amsterdam, ITA chose not to re-broadcast their previous shows online, but to have the ITA ensemble as well as other famous Dutch actors take part in a reading marathon of Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron. The 14th century novella is structured as a frame story, with 10 young men and women spinning together 100 tales while sheltering in a villa outside Florence during yet another pandemic — the Black Death. The recordings of Dutch actors reading these tales were published on the ITA website over a 70-day period during the lockdown in the Netherlands. (For more details, please click here)

Van Hove expresses awe for the ten characters in the original story. “They keep their lives disciplined, always getting up at 7:30 in the morning and having lunch and washing the dishes at the same time every day. The same discipline as always. That’s the first thing they do. The second thing is, every evening, they have to tell a story not just for entertainment, but also a story that makes you forget as well as not forget. After ten days and 100 tales, they leave and go back home.”

“They survive by telling stories, which gives them a bit of release and relief […] The stories are sometimes brutal, sometimes sexual, sometimes sensual, but also have a bit of an uplifting feeling.”

“I wanted to give this to the Netherlands, making it a 70-day event, thinking hopefully, by then, the pandemic would be over.”

And right at the 70-day mark, Amsterdam re-opened.